Ever wondered the purpose of those mysterious never-used keys on your keyboard? Read on...

The forgotten Scroll Lock key

My new Rasperry Pi 400 doesn't have a Scroll Lock key. This makes me uncomfortable and I demand justice for this neglected key.

The problem with Scroll Lock is that it's always been a good idea, but its purpose has been so misunderstood that it has never quite been implemented to its full potential, even though it seemed a logical solution to an old usability problem.

For example, in a non-GUI Linux console, Scroll Lock temporarily freezes the output on the screen. (On old DOS systems that was the function of the Pause key.) For applications that react to scroll lock at all, the function of the key usually manipulates the functionality of that program.

To understand what Scroll Lock is for, take a look at Num Lock and Caps Lock. Both of these keys work by manipulating the behaviour of a set of keys on the keyboard itself. Since the late 1980s, a typical PC keyboard has two sets of arrow keys, but the earlier "Standard" keyboard layout had only one set of arrow keys that worked in tandem with the numeric keypad. The purpose of the Num Lock key was to switch between being able to type numbers quickly, and being able to access the arrow keys.

The IBM Model F keyboard from the early 1980s. Note the lack of dedicated cursor keys, and the Num Lock and Scroll Lock keys for switching the mode of the numeric keypad. (Public domain image, source: Wikimedia Commons)

In the days before computer mice became commonplace, the intent of Scroll Lock was to determine whether the arrow keys on the keyboard should be for scrolling or for moving the text cursor (carat) around. Scroll Lock was meant to convert the arrow keys from "move cursor up," "move cursor down," etc. into "scroll up", "scroll down", etc. A bit like what the scroll wheel does on your mouse today.

Of course, newer keyboard layouts (beginning with the IBM Model M keyboard in 1985) often feature two sets of arrow keys, a dedicated bank of navigation keys (with the Scroll Lock key above it) and a combination numeric keypad bank (with a Num Lock key in the top corner). It's hard to know who was thinking what at the time, but the logical evolution at this point in time would have been for the Scroll Lock key to turn one set of arrow keys into scrolling keys, while the other set continued to function as usual.

The IBM Model M keyboard, introduced in 1985. (Public domain image, source: Wikimedia Commons)

It's worth mentioning that some variations of these keyboards, intended for IBM dumb terminals rather than PCs, had the cursor keys labelled with both the usual arrow directions, and alternate functions such as "roll up", "roll down", etc. This indicates that there were systems where the user could select scrolling behaviour for the cursor keys, although not in the PC world.

When GUIs appeared, things took a different direction. The original Apple Macintosh didn't include arrow keys at all (Steve Jobs believed that users would avoid using a mouse unless they were forced). Into the 1990s, users got used to the idea that scrolling could only be done with a mouse while cursor movements could be done with the keyboard. Until MacOS 9, the arrow keys of Macintosh computers moved the cursor while Page Up and Page Down scrolled the contents of the screen without moving the cursor.

Today the behaviour of the arrow keys is purely application specific. Some software like Microsoft Excel does indeed implement the Scroll Lock key as a means of switching the arrow keys to scrolling keys, but we never got the full potential of being able to have both scrolling keys and cursor keys on the keyboard at the same time, despite decades of keyboards being built with two sets of navigation keys, one set having a Scroll Lock key above it. Instead, both sets of arrow keys on the keyboard get switched to the same scrolling functionality and you need to turn scroll lock back off again to change the selected cell in your spreadsheet.

Ultimately, we ended up with a bunch of other solutions. Mice got scroll wheels. Today's word processors simply require the user to reach for the mouse for scrolling and there's no way to switch modes on the keyboard. Today's Web browsers default to using the navigation keys for scrolling but have adopted the F7 key to do what the Scroll Lock key was meant to do and allow you to use the arrow keys for carat browsing. But most web designers never designed their sites with that in mind, so it doesn't work that great.

It's weird to think that the intended key for this kind of functionality was thought of decades ago and has been sitting right there on our keyboards... unused... all this time...

The mysterious SysRq key...

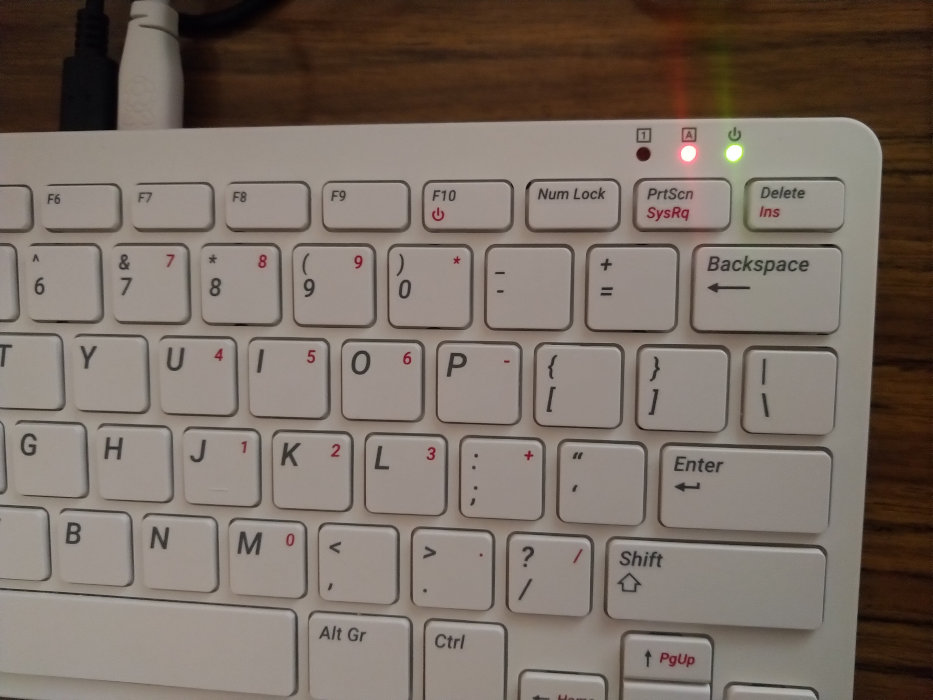

Ever wondered about that mysterious SysRq, or 'System Request' key on your PC keyboard?

It first appeared on PC keyboards in 1984, with the idea that you would hit that key to access a screen with various OS functions without quitting your current app.

Desktop OSs of the day didn't have multitasking so you normally had to quit your current app to get back to your OS.

The potential of the SysRq key was never realised. It was never implemented at the time.

So in such a primitive era, how was this key intended to work? The idea was when you pressed it, your current running app wouldn't see that keystroke. Instead, it would trigger a special 'interrupt' registered in the CPU.

Interrupt? What does that mean? It goes something like this:

- After a PC boots up, the OS code is loaded into RAM.

- The CPU runs the OS (and anything else) by stepping through and jumping around between different sections of code in RAM.

- Imagine the CPU having a tiny piece of memory inside, (called an interrupt register) that can store the memory address of a special place in RAM.

- When SysRq gets pressed, the CPU remembers its current position in RAM, jumps to the special memory address, and starts running OS code from that spot.

- When the user finishes playing with the OS and wants to return to their app, the CPU jumps back to the memory address it had saved earlier and keeps running the original app like nothing had happened.